Sixty years before that, we would have seen many wells all over Hagåtña.

Before the Naval Government made available a modern water supply system, there were only THREE WAYS the people of Hagåtña got fresh water :

1. THE HAGÅTÑA RIVER AND FONTE RIVER (SÅDDOK)

Luckily, a river flowed right through the heart of the city, starting at the spring (Måtan Hånom) to the east in the Dedigue area and moving right through the capital till it emptied into the sea at the entrance of Aniguak. But the river water was never used for drinking. People did the laundry in the river. Animals did their business there, too, and all kinds of pollutants made river water dangerous to drink.

The Fonte River was untouched by human activity but one had to walk half a mile or more to Fonte with your water containers. It was done, but Fonte was never a major source of water for Hagåtña in the old days.

2. RAIN WATER (HÅNOM SINAGA)

This is the water most people drank in those days. The custom was to place large containers, wood, clay and less frequently metal, under the eaves of roofs and catch the rain water. The problem was the dry season. Stored water would eventually dry up if it didn't rain at all for a while. Most times it rained even just a bit during the dry season, but sometimes it did not.

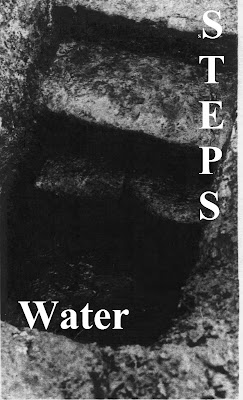

3. WELLS (TUPU')

Hagåtña sits on limestone soil, pictured above. The good thing about limestone soil is that it allows rain water to percolate down into the ground till it forms an underground lake. Dig a well and you can tap into that subterranean lake.

The bad thing about limestone soil is that the rain water picks up the chalky, white dust of the limestone. You dig a well and find water, but it is chalky, heavy and brackish. If you put well water into a clear glass, you will see a cloudy, dull gray liquid. Keep drinking that chalky water and in time you might develop kidney stones, among other potential problems.

The other, more serious problem with limestone soil is that rain water that falls on contaminated soil will carry those impurities down to the underground lake. Animals of all sorts lived in Hagåtña, around houses and even under houses. Those animals used the bathroom right on the ground, so fecal matter and urine seeped into the soil and into the underground lake.

Besides animal waste, there was also no indoor plumbing, so people also went to the bathroom outside but in the privacy of outhouses. Still, all that human waste also seeped into the ground. All kinds of waste water was thrown out on the ground.

Durante unas obras de construcción en Agaña en 1972, los obreros descubrieron un pozo anterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

Sesenta años antes de eso, habríamos visto muchos pozos por toda Agaña.

Antes de que el Gobierno Naval de EE.UU. pusiera a disposición un moderno sistema de suministro de agua, solo había TRES FORMAS por las que la gente de Agaña obtenía agua dulce:

1. EL RÍO HAGÅTÑA Y EL RÍO FONTE (SÅDDOK)

Afortunadamente, un río atravesaba el corazón de la ciudad de Agaña, comenzando en el manantial (Måtan Hånom) hacia el este en el área de Dedigue y atravesando la capital hasta desembocar en el mar a la entrada de Aniguak. Pero el agua del río nunca se utilizaba para beber. La gente lavaba la ropa en el río. Los animales también hacían su trabajo allí, y todo tipo de contaminantes provocaba que el agua del río fuera peligrosa y no apta para el consumo humano.

El río Fonte no fue alterado por la actividad humana, pero uno tenía que caminar media milla o más hasta Fonte con sus recipientes para el agua. Se hacía a veces, pero Fonte nunca fue en aquellos años, un suministro importante de agua para Agaña.

2. AGUA DE LLUVIA (HÅNOM SINAGA)

Ésta era el agua que la mayoría de la gente bebía en aquella época. La costumbre era colocar grandes recipientes, de madera, barro y con menos frecuencia de metal, bajo los aleros de los tejados y recoger el agua de la lluvia. El problema se presentaba durante la estación seca. El agua almacenada eventualmente se secaría si no llovía durante un tiempo. La mayoría de las veces durante la estación seca llovía aunque fuera un rato, pero a veces no era así.

3. POZOS (TUPU ')

Agaña se asienta sobre suelo de piedra caliza. Lo bueno del suelo de piedra caliza es que permite que el agua de lluvia se filtre hacia el suelo hasta formar un lago subterráneo. Cavemos un pozo y podremos acceder a ese lago subterráneo.

Lo malo del suelo de piedra caliza es que el agua de la lluvia arrastra el polvo blanco y calcáreo de la piedra. Cavamos un pozo y encontramos agua, pero es calcárea, pesada y salobre. Si ponemos agua de un pozo en un vaso transparente, veremos un líquido gris opaco y turbio. Si seguimos bebiendo de esa agua calcárea, con el tiempo podríamos desarrollar cálculos renales, entre otros problemas de salud.

El otro problema serio del suelo de piedra caliza es que el agua de la lluvia que cae sobre el suelo contaminado transportará esas impurezas al lago subterráneo. Animales de todo tipo vivían en Agaña, alrededor de las casas e incluso debajo de las casas. Esos animales hacían sus necesidades directamente en el suelo, por lo que la materia fecal y la orina se filtraban en el suelo y en el lago subterráneo.

Además de los desechos animales, tampoco había aseos en el interior de las viviendas, por lo que la gente también iba al baño afuera aunque en la privacidad de las dependencias. Aún así, todos esos desechos humanos finalmente se filtraban al subsuelo. Todo tipo de aguas residuales se arrojaban al suelo.

Así que en la medida de lo posible, la gente evitaba beber agua del pozo. Sin embargo, algunas personas recurrieron a beber agua del pozo para que los funcionarios del gobierno, tanto españoles como estadounidenses, se quejaran de que los pozos de Agaña estaban contaminados y la gente se estaba enfermando de disentería y otros males.

Si no era conveniente beber agua del pozo, ¿para qué excavar uno? Pues bien, el agua del pozo se usaría para casi todo lo demás. Asearse, lavar las ollas y sartenes, regar las plantas, hacer la limpieza general e incluso la ropa sucia si se quería evitar ir a lavar al río. A veces se podía cocinar utilizando el agua del pozo, según la comida. Aunque incluso los animales podían enfermarse por el agua del pozo contaminada, el pozo era muchas veces el único suministro de agua para el consumo de las personas. Mencionábamos antes que incluso la gente a veces se arriesgaba y bebía agua del pozo.

EL DESCUBRIMIENTO DE 1972

El pozo descubierto involuntariamente en 1972 tenía 4 y 3/4 pies de profundidad desde la superficie del suelo, en el momento en que se estaba utilizando el pozo, y estaba cuatro pies más bajo que la superficie del suelo en 1972. Es por eso que los arqueólogos tuvieron que cavar bastante. La superficie del suelo siempre está elevándose y lo antiguo siempre enterrándose.

Tres lados del pozo fueron revestidos por expertos con roca cincelada, para evitar que la caliza calcárea afectara al agua, en la medida de lo posible. Se colocaron escalones de piedra en el cuarto lado para permitir que una persona descendiera al pozo y llenara un balde con agua.

No se sabe cómo podrían haber continuado las obras de construcción y aún así salvar el pozo como una reliquia del pasado, pero el pozo fue finalmente tapado.

El pozo estaba ubicado en el límite entre los lotes 385 y 383, siendo estos lotes propiedad de Juan Díaz Torres y María Aflague Castro respectivamente, en el barrio de San Ignacio, entre las calles María Ana de Austria y Pavía. Hoy, ésta es la zona de Pedro's Plaza al oeste del recinto GPD (la comisaría) de Agaña. El pozo podría haber sido utilizado por ambas casas, y tal vez incluso por otros vecinos.

No comments:

Post a Comment