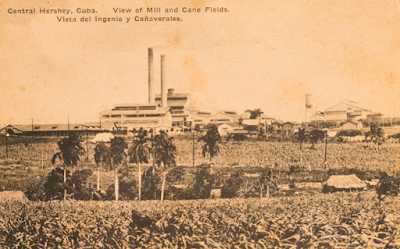

Street scene in Luta during Japanese times

Reinhold Atalig Mangloña, as his first name suggests, was born in Luta (Rota) when there was still a German priest there. He was baptized Reinhold, a German name, but Chamorros also Hispanicized it to Rainaldo.

But the Japanese had just come to the Northern Marianas and the Japanese language and culture were about to influence the Chamorros of Luta and Saipan in a very big way.

Reinhold went to school and learned the following story from his Japanese teacher, a woman. It was shared with me by his son Richie Mangloña and the text is Richie's own spelling and wording. The English translation is mine.

The moral of the story : respect the elderly as sources of wisdom.

Gi tiempon antigo giya Hapon, eståba ti man ma gef polu' i

manåmko'-ñiha

(In ancient times in Japan, they did not really consider their

elderly)

komu man gai båli osino man malåte'.

(as having any worth or else as being intelligent.)

I manaotao Hapones sesso man ma fa'tinåsi kuåtto i manåmko'-ñiha

(Japanese people often made rooms for their elderly)

gi santåtten guma' pat gi la chågu' ginen i gima'-ñiha

(in the rear of the house or farther away from their houses)

putno u fan ma atendin maolek sa' ma po'lu na esta meggai-ña

(so as not to attend to them well because they considered

that they were more)

estotbun-ñiñiha ki todu i prubechu.

(of a bother rather than a benefit.)

Pues guaha un familia mañåsaga Hokkaido'.

(So there was a family living in Hokkaido.)

I tåta as Mitsuro, i nåna as Mikki, i hagan-ñiha as Eiko yan

si nånan-biha as Mio.

(Mitsuro was the father, Mikki the mother, Eiko their

daughter and Mio the grandmother.)

Ma na' såsaga si nånan-biha gi dikiki' na kuåtto gi

tatten-guma'.

(They housed grandmother in a small room behind the house.)

Un dia sigi umesalao i taotao i Impiradot na para u guaha

kumpitensia

(One day the Emperor's people kept shouting that there was

to be a contest)

para todu i famagu'on eskuela ya i håyi gumånna

(for all the school children and whoever won)

para u ma nå'i dångkulu na premiun salåpe'!

(would be given a large prize of money!)

Magahet si Mitsuro sumen popble ya ha tåtanga na puedde u

gånna

(Truly Mitsuro was very poor and he wished that perhaps)

i hagå-ña i premiu

komu ha na' saonao gi kumpitensia!

(his daughter would win the prize if he made her participate

in the contest!)

Infin humalom i påtgon Mitsuro gi kumpitensia ya man ma na'i

hafa para u ma cho'gue.

(At last Mitsuro's child entered the contest and they

were given what they were to do.)

I kuestion nai man ma presenta i famagu'on ilek-ña,

"Haftaimanu nai siña

(The question which was presented to the children said, "How

can

en na'halom i hilun man laksi gi esti i gai maddok na alamli

nai

(you put the sewing thread into the hole of this wire which)

ma chaflilik gi todu direksion ya para un na'huyong gi otro

banda?"

(twists in all directions so that you make it come out on the other

side?")

Ha chagi i påtgon todu i tiningo'-ña lao ti siña ha na'

adotgan

(The child tried with all her knowledge but could not run

through)

i hilu ginen i un måddok esta i otro.

(the thread from one hole to the other.)

Ni si Mitsuro yan i asagua-ña ti ma tungo' taimanu para u ma

cho'gue este na chagi.

(Not even Mitsura and his wife knew how to do this attempt.)

Esta ma po'lu na imposipble esti para u ma cho'gue ya man

triste i familia

(They already figured that this was impossible to do and the

family was sad)

sa' ma hasso na ti siña ma gånna i premiu.

(because they thought that they couldn't win the prize.)

Pues annai man matata'chong gi kusina mañochocho un oga'an, ha

lipåra si Eiko

(So when they sat down eating in the kitchen one morning,

Eiko noticed)

na man guaguasan si nånan biha gi hiyong i kuatto-ña gi

lachago' na distansia.

(that grandmother was trimming outside her room at a far

distance.)

Ilek-ña, "Nangga ya bai faisen si nanan-biha kao ha

tungo' taimanu nai siña

(She said, "Wait and I will ask grandmother if she

knows how it is possible)

ta na' adotgan esti i hilu guini na alamli".

(for us to push the thread through the wire.")

Man oppe ha' si Mitsuro, "Esta ennao i biha maleffa,

hafa gue' ennao tiningo'-ña!".

(Mitsuro answered, "The old lady already forgot that,

what does she know about that!")

Ti man osgi si Eiko, ha bisita guato si bihå-ña ya ha

faisen. Ilek-ña si Mio,

(Eiko didn't obey, she visited her grandmother and asked

her. Mio said,)

"Ai iha na linibiåno ennao i finaisesen-mu. Fan aligao

oddot agaga' ya

("Oh daughter what you are asking is so easy. Look for

red ants and)

un godde i tataotao-ña nai hilun man laksi.

(tie its body with the sewing thread.)

Na' hålom gi halom i måddok pues po'luyi asukat i otro banda

(Put it through the hole then put sugar for it on the other

side)

sa' siempre ha tatiyi i pao asukat ya humuyong gi otro

bånda!"

(because for sure it will follow the smell of sugar and go

out the other side!")

Ha cho'gue si Eiko i tinago' i biha ya magahet macho'cho'!

(Eiko did grandmother's instruction and it truly worked!)

Ha håla magahet i oddot i hilu ginen i un båndan i alamli

esta i otro banda!

(The ant really pulled the thread from one side of the wire

to the other side!)

Sumen magof si Eiko!

(Eiko was really happy!)

Måtto i ha'ane para u ma presenta i famagu'on håfa

ineppen-ñiha guato gi Impiradot!

(The day came for the children to present their answer to the

Emperor!)

Meggai chumagi man man na'i ineppe lao ti kumfotmi i Imperadot.

(Many tried to give an answer but the Emperor didn't agree.)

Annai måtto tarea-ña si Eiko, ha fa'nu'i i Imperadot taimanu

ma cho'gue-ña.

(When it came to Eiko's turn, she showed the Emperor how it

is done.)

Mampos manman i Imperadot ya ha faisen i påtgon.,

(The Emperor was really amazed and asked the child,)

"Kao hagu ha' esti humasso para un cho'gue pat ma ayuda

hao?"

("Was it only you who thought of doing this or were you

helped?")

Ti yaña si Eiko mandagi pues ilek-ña, "Ahe', si bihå-hu

yu' fuma'nå'gue!".

(Eiko didn't like to lie so she said, "No, my

grandmother taught me!")

Annai ha tungo' i Imperadot na ayu i un biha sumåtba i

finaisen-ña na kuestion,

(When the Emperor knew that it was one old lady who solved

the question he asked,)

ha rialisa na lachi eyu na hinengge i para u fan ma

chachanda i manåmko'!

(he realized that it was wrong thinking to be rejecting the

elderly!)

Ginen eyu na tiempo, ha otdin na debi todu i manåmko' Hapon

(From that time, he ordered that all the elderly of Japan)

ufan ma atiendin maolek ya u fan ma setbi komu siha

kumåkatga i ancho na kinimprendi.

(were to be attended to and served well as being the ones

who carried broad understanding.)

Magof si Eiko' annai man siha yan si Nånan-biha ta'lo gi

halom guma'

(Eiko was happy when she was together again with grandmother

in the house)

ya kada dia ha atendi komu guiya i tesorun i familia!

(and she took care of her as being the treasure of the family!)

Reinhold Atalig Mangloña

1917 ~ 2002

NOTE

Hapon/Hapones are the older Chamorro words for "Japan" and "Japanese," borrowed from Spanish. More recently, especially among Chamorros from Guam, American influence has brought into the language the word Chapanis for "Japanese."