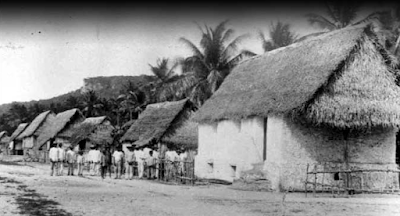

SONGSONG, LUTA IN GERMAN TIMES

Luta had a population of around 450 people in German times, from 1899 till 1914. Only one school was needed for such a small population, as the majority of the children under 18 didn't go to school even if there were one. In 1907, it was reported that there were 30 students in Luta's school, definitely a far cry from the number of school-age children.

But those were different times. As in the rest of the Marianas, people wondered just how much education a child of the islands needed when most were destined to till the soil and fish within the reef as their fathers and grandfathers were doing. It sometimes happened that girls especially were not sent in large numbers to school and as soon as the girls reached puberty, they were yanked out of school by their parents to keep them "safe."

So, 30 students in 1907 can be understood given the mentality of the time. These were probably younger children, who were taught to spell, count, read, write or at least write their names. Under the Spanish government, the Catholic religion would also have been taught, but not under German rule. It's even doubtful that the children learned German; their teacher was Chamorro who was paid 50 Marks a month and lived rent-free in a modest government residence.

There is talk of a "ma'estron Taitano" in some of the documents of the time. This is probably José Mangloña Taitano, whose father was from Guam and whose mother was from Luta. He was a teacher and also a lay leader of the Luta parish.

For whatever reason, the German colonial government closed the government school in Luta in May of 1910.

The German priest of Luta, Father Corbinian Madré, Capuchin, saw this is an opportunity to fill in the gap. He announced to the parents of Luta that he was willing to run his own school, without pay, as long as the parents agreed to build a school house. This they did, gathering whatever wood and supplies they could.

The government did not lift a finger. All the government did was lend some school desks now and then.

The work didn't take long and Father Corbinian began teaching on July 26. He divided the students into a higher level for older children (up to fourteen) and a lower level for children as young as seven. In total, he was teaching 95 students, triple the number of students when the government ran a school in 1907.

FATHER CORBINIAN

The German priest of Luta 1908 to 1919

"KASTIGA GUE' MÅS!"

Father focused on teaching German, math, reading and writing. He found that teaching German was easiest for the children. Arithmetic was not so easy for the students especially the girls, according to him. Reading and writing were also challenging. He found that the attention span of the students was short, and it tired him out to keep their attention by entertaining them in some way.

But the priest felt his work was not all in vain. He mentioned that some students who reached 14 years and were not supposed to stay in school came by anyway, wanting to learn some more.

THE SCHOOL CLOSES

Although the Japanese allowed Father Corbinian to remain on Luta till 1919, I can't imagine they allowed him to continue his school, teaching German, assuming the school was still open in 1914. But, whatever year it closed, it was definitely closed by the time the missionary left Luta for good.

VERSIÓN EN ESPAÑOL

(traducida por Manuel Rodríguez)

CUANDO CERRARON LA ESCUELA DE ROTA

La isla de Rota (Luta, en chamorro) tenía una población de

alrededor de 450 personas durante la época alemana, desde 1899 hasta 1914. Solo

se necesitaba una escuela para una población tan pequeña, ya que la mayoría de

los niños, menores de 18 años, no iban a la escuela. En 1907, se informó que

había 30 estudiantes en la escuela de Rota, definitivamente cifras muy alejadas

de la cantidad de niños en edad escolar.

Pero ésos eran tiempos diferentes. Como en el resto de las

Marianas, la gente se preguntaba cuánta escolarización necesitaba un niño de

las islas cuando la mayoría de la población se dedicaba a cultivar la tierra y

pescar dentro del arrecife como lo hacían sus padres y abuelos. A veces sucedía

que las niñas, especialmente, no eran enviadas en gran número a la escuela y,

tan pronto como llegaban a la pubertad, sus padres las sacaban de allí para

mantenerlas "seguras".

Entonces, 30 estudiantes en 1907 se puede entender como algo

normal dada la mentalidad de la época. Probablemente eran niños pequeños, a

quienes se les enseñaba a deletrear, contar, leer, escribir o al menos escribir

sus nombres. Bajo el gobierno español, la religión católica también se había

enseñado, pero no bajo el dominio alemán. Incluso es dudoso que los niños

aprendieran alemán; su maestro era chamorro, a quien le entregaban 50 marcos al

mes y vivía sin pagar alquiler en una modesta residencia del gobierno.

Se habla de un tal "ma'estron Taitano" en algunos

de los documentos de la época. Probablemente sea José Mangloña Taitano, cuyo

padre era de Guam y cuya madre era de Rota. Era maestro y también líder laico

de la parroquia de la isla.

Por alguna razón, el gobierno colonial alemán cerró la

escuela gubernamental en Rota en mayo de 1910.

El sacerdote alemán de Rota, el padre Corbinian Madré,

capuchino, vio que ésta era una oportunidad para llenar aquel vacío. Anunció a

los padres de los niños de Rota que estaba dispuesto a administrar su propia

escuela, sin cobrar, siempre y cuando los padres acordaran construir un

edificio escolar. Esto lo hicieron, juntando cualquier madera y suministros que

pudieron.

El gobierno no movió un dedo. Todo lo que hizo el gobierno

fue prestar algunos pupitres de vez en cuando.

El trabajo no tardó mucho y el Padre Corbinian comenzó a

enseñar el 26 de julio. Dividió a los estudiantes en un nivel superior para

niños mayores (hasta catorce) y un nivel inferior para niños de tan solo siete

años. En total, estaba enseñando a 95 alumnos, triplicando el número de

estudiantes cuando el gobierno dirigía la escuela en 1907.

El Padre Corbinian escribía boletines de calificaciones, que

los padres tenían que devolver. Un padre escribió: "Kastiga gue

'mås!" "¡Castígalo más!" Ésos eran los días en que los padres

querían que otros adultos castigaran a sus hijos, ya fuese en la escuela, en la

iglesia o en la calle.

Padre Corbinian se centró en la enseñanza del alemán, las

matemáticas, la lectura y la escritura. Descubrió que enseñar el alemán era lo

más fácil para los niños. La aritmética no era tan fácil para los estudiantes,

especialmente para las niñas, según él. Leer y escribir también era un desafío.

Descubrió que la capacidad de atención de los estudiantes no era grande, y se

cansaba de mantener su atención entreteniéndolos de alguna manera.

Pero el sacerdote sintió que su trabajo no era en vano.

Mencionó que algunos estudiantes que alcanzaron los 14 años y no debían

quedarse en la escuela, venían de todos modos, queriendo aprender un poco más.

Los japoneses se hicieron cargo de la isla de Rota y el

resto de las Marianas alemanas, en octubre de 1914, cuando estalló la Primera

Guerra Mundial. Japón estaba del lado de los aliados esa vez y contra Alemania.

Aunque los japoneses permitieron que el Padre Corbinian

permaneciera en Rota hasta 1919, no puedo imaginar que le permitieran continuar

con su escuela, enseñando el alemán, suponiendo que la escuela aún estuviera

abierta en 1914. Pero, en cualquier año que hubiese cerrado la escuela, sin

lugar a duda no existía cuando el misionero abandonó definitivamente la isla de

Rota.