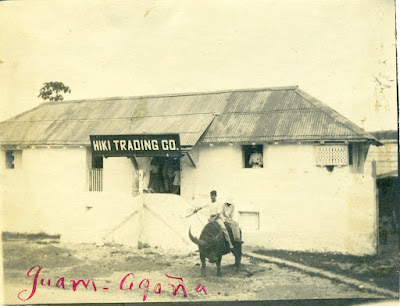

THE HIKI TRADING COMPANY

Hagåtña in the early 1900s

By the 1890s, Japan started to take an increased economic interest in the Pacific, both in wanting to get things from the islands and nations of the Pacific Rim, and also to sell to them. Copra, the dried meat of coconuts, was one Pacific commodity in demand. The oil obtained from it could be used in many commercial products, and the meat used as a food product for both man and beast.

The islands of Micronesia could supply that copra, but the Japanese could also supply the islands. Japan was closer to the islands than the US or other Western countries to sell Western products. Merchandise did make it to the Marianas from both east and west; goods could be bought in Manila and shipped to the Marianas, but ship transportation was not steady nor frequent. American and other goods did come from Hawaii and the US, but usually on whaling ships and the occasional commercial ship, but again these were not consistent nor frequent. But the Japanese could ship merchandise to the Marianas on a regular basis if the market proved successful.

The Japanese started to "open shop," as it were, in Micronesia in the 1890s. In 1899, Spain was no longer on the scene, having sold Guam to the US and the rest of Micronesia to the Germans. The Germans were initially not very pleased with the many Japanese merchants coming in and out of Micronesia, but the Americans on Guam were more accommodating. By 1899, Japanese merchant ships were already providing passenger transportation to and from Guam. By the early 1900s, the Japanese merchant presence on Guam was so strong that people claimed that the Japanese had a monopoly on trade on the island. While other races did operate stores, the Japanese were undeniably the strongest commercial force on island at the time.

One of the Japanese companies doing business on Guam in the early 1900s was the Hiki Trading Company.

Haniu was appointed Manager of the Guam branch in 1902

The Hiki Company's schooners would also transport passengers up and down the Marianas. In the period 1900 to 1914 many Chamorros from Guam migrated to Saipan. The Hiki schooner was one way to get there. José Shimizu also transported passengers up and down the Marianas. Most of that migration ended in late 1914 when the Japanese took over the Northern Marianas from Germany.

Around 1900, the Guam branch of Hiki was managed by José T. Shibata, from Nagasaki. He had married a Chamorro, Vicenta Cruz Herrero. By 1902, the company had appointed a man from Tokyo, Hikoshiro Haniu, as manager of the Guam store. Haniu later married a Chamorro, Maria Deza Blaz, and was baptized a Catholic to do so, taking the Christian name José. His descendants, many of whom are better-known as the familian Desa, remain.

Around 1900, the Guam branch of Hiki was managed by José T. Shibata, from Nagasaki. He had married a Chamorro, Vicenta Cruz Herrero. By 1902, the company had appointed a man from Tokyo, Hikoshiro Haniu, as manager of the Guam store. Haniu later married a Chamorro, Maria Deza Blaz, and was baptized a Catholic to do so, taking the Christian name José. His descendants, many of whom are better-known as the familian Desa, remain.

JOSÉ HIKOSHIRO HANIU