The Our Father in Chamorro

according to Sanvitores in 1668

On this Father's Day, someone asked me, "Is tåta a true Chamorro word?"

The inquirer points out that tata is used by many Hispanics clear across the Pacific Ocean in Central and South America.

Among our own Austronesian cousins, who share many words, grammar and other features with us, the word tata is rarely the word for "father." Far more common is ama and tatay. In some Austronesian languages, tatay is the informal way of addressing a father while ama is the formal title for a father.

Given the wide variety of Austronesian words for "father," including ama, sama, tama, baba and dozens of other forms, including the occasional tata, it could be that Chamorro is one of those rare Austronesian languages where tåta is the indigenous word for "father." That Tagalog speakers and other Filipinos use tatay, sometimes as the informal word and sometimes as the actual word for "father," makes one suspect that tata and tatay are two forms of the same word. And, yes, even tata is used by some Filipinos as an informal form of "father."

In Latin America, where tata is often an informal way of addressing a father, people do not speak Austronesian languages. Yet, it shouldn't surprise us that tata is said there, and for two reasons. Firstly, tata is also used by other languages all around the world, besides Austronesia and Latin America. Tata is the informal word for "father" in different languages and dialects in Europe and in Africa, for example.

Secondly, a large number of words for "father" in the different languages across the globe are variations of the a-a form. Dada, baba, papa and tata all follow this.

So it seems that our ancestors could very well have used the word tåta for "father," just as we find it in many languages in every corner of the world.

THE FIRST VERSION OF THE "OUR FATHER"

But then I remembered this. Just to add to the mystery.

When Sanvitores came to Guam in 1668, he obviously needed to teach the people Catholic prayers in their own language. Therefore, as early as 1668, there should have been a Chamorro version of the Our Father, in the Chamorro spoken back then, which would have been free of foreign words except for a few words where the native language may have lacked them. But "father" should not be one of these words, since every one has a father! So....how did Sanvitores translate "Our Father" into Chamorro in 1668? That should clear up, without a doubt, what the certain Chamorro word for "father" is.

OUR SUPERIOR WHO ART IN HEAVEN

I'm afraid Sanvitores' rendering of "Our Father" provokes more questions than provides answers.

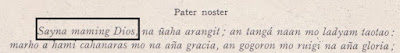

As you can see from the picture at the top of this post, Sanvitores' opening words of the "Our Father" are :

SAYNA MAMING DIOS

That should mean "Our Father." Instead it means "Our superior God."

Two words are easily recognizable; the Chamorro Sayna, spelled today as saina. And the Spanish Dios, meaning "God."

Saina can be applied to many people. The fundamental meaning of saina is "superior," someone higher in status than you. It has nothing to do with age. On occasion, a nephew will actually be older in age than his uncle. Still, the 15-year-old uncle is saina to his 16-year-old nephew. "Uncle" trumps age when it comes to status.

A 40-year-old priest will be called saina by an 80-year-old woman. Priesthood trumps age (in traditional Chamorro culture) when it comes to status.

The word maming is måme (ours, exclusive) if you think about it. Why then did Sanvitores add the ng? Probably because he learned his rudimentary Chamorro from a shipwrecked Filipino who lived on Guam for seventeen years before he was picked up by a passing Spanish ship and taken back to the Philippines. It is possible that this Filipino retained traits of his native Filipino language and mixed it with his newly acquired (and possibly rough) Chamorro. Sanvitores wrote this version of the Our Father in Chamorro before he even landed on Guam, Sanvitores himself wrote that he had to make corrections in these early writings in Chamorro.

NO "TÅTA?"

So the question is, "Why didn't Sanvitores use tåta when translating 'our father?'"

Even if his Filipino tutor spoke "broken Chamorro," surely the Chamorro word for "father" would be so commonly spoken in ordinary conversation that the Filipino couldn't get that one wrong!

So now we can speculate that perhaps our ancestors did not say tåta for "father," otherwise, why didn't Sanvitores use it?

Check out this other little piece of evidence :

When Sanvitores wanted to translate into Chamorro "Holy Mary, mother of God," he wrote the above words. Most of the words are easily recognizable as the following :

Santa Maria, saina palao'an ni Jesucristong Dios

Holy Mary, woman superior of Jesus Christ God

Once again, some traits more Filipino than Chamorro (at least modern Chamorro) are seen. We don't say ni to mean "of," at least, not any more. But this is exactly what is said in Filipino. And we see once again the -ng ending (in Jesucristo) which isn't done in Chamorro (at least anymore) but which is done in Filipino.

But the main thing to notice here is that Sanvitores translates "mother" as saina palao'an.

This would suggest that "father" is saina låhe, a term which is found, in fact, in the rest of Sanvitores' writing.

So, one theory could be that our ancestors did not say tåta and nåna, but rather saina låhe and saina palao'an. Tåta and nåna could have come into the language later, maybe from Filipino influence (tatay and nanay) or Latin American influence.

YES "TÅTA," BUT NOT FOR PRAYER

But here's another theory.

Perhaps our ancestors did say tåta and nåna. Then why didn't Sanvitores use those terms in his Chamorro writing?

It's possible that tåta and nåna were considered too informal, like "daddy" and "mommy." Among Tagalog speakers, one constantly hears tatay and nanay in ordinary speech. But when Filipino people pray the Our Father, they switch to the formal word ama for "father."

Perhaps this is also what happened when Sanvitores wrote his version of the Our Father and his other religious writings. In time, perhaps, the missionaries and people switched to using tåta in prayer when the religion was securely established in our islands.

Tåta is found in Chamorro word lists going back to the early 1800s and for centuries now we've been saying Tåtan-måme, and not Sainan-måme, when we say "Our Father."

Until we find more Chamorro writing of the time, which is a remote possibility, we can't be certain at all about these questions for the time being.

Hi Påle,

ReplyDeleteI remember reading somewhere that suggested that nana and tåta may also be Aztec in origin. The Nahuatl word for father is tahtli and mother is nantli. Not exact to our tåta and nåna, but similar. High possibility considering the Spanish brought many people from Mexico to the Marianas and Philippines that also had indigenous blood.

There was also the argument that Austronesian languages are not gender specific and we'd say saina to refer to either father or mother, che'lu for either brother or sister and context would define the gender.

Linguistic history is so hard to get exact. There are so many possibilities. But always fascinating nonetheless.

Si Yu'us ma'åse,

Si Kindo