It's interesting how a little-known bit of personal history can become a song sixty or more years later, sung in a different place by people unconnected to the event.

The song deals with a Spanish Capuchin missionary in Yap in the late 1890s and early 1900s. His name was Father Daniel de Arbácegui. In Chamorro, Daniel is pronounced Daniet.

There was a small community of Chamorros living in Yap since Spanish times and they were close to the Spanish missionaries.

A young boy of around 6 years of age lost both parents and was then raised by Påle' Daniet. But then the Germans took over Yap and the Spanish missionaries had to go. At some point, the little boy moved to Saipan, but nothing more for certain is known about him.

The story was kept by Juan Sanchez, a writer, poet and storyteller in Saipan who was very close to the clergy. Alex Sablan, the composer and singer of the song, learned the story from Sanchez.

There was one other boy in Micronesia raised by the Spanish Capuchins. His name was Miguel de la Concepcion. Was this the boy raised by Påle' Daniet? I have my doubts.

First of all, the boy in the song was from Yap whereas Miguel de la Concepcion was from Ponape. Påle' Daniet, too, was a missionary in Yap and never stayed in Ponape, where Miguel was from. Finally, the boy in the song moved to Saipan, but Miguel moved to Manila where he continued to be raised by the Spanish friars there. But...I think we should leave some room for the possibility that the orphaned boy in question is Miguel de la Concepcion and that, as often happens, the oral information passed from person to person, got some details mixed up.

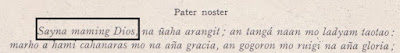

Sais åños ha' trabia i idåt-ho annai kinenne' as Yu'us i dos saina-ho.

(My age was only still 6 years when God took my two parents.)

Ya si Påle' Daniet pumoksai yo'; dumångkulo yo' gi gima' misionårio.

(And Father Daniel raised me; I grew up in the house of a missionary.)

Hu nånå'e gråsia si Yu'us pot i yino'åse' Påle' Daniet.

(I give thanks to God for the kindness of Father Daniel.)

Guiya kulan tahguen i dos saina-ho. Si Påle' Daniet pumoksai yo'.

(He was like the replacement of my two parents. Father Daniel raised me.)

Idåt. Age. From the Spanish edad. Some people spell it and pronounce it edåt.

Yino'åse'. The more usual rendering is yine'ase'.

CANCIÓN A PADRE DANIEL

Es interesante cuando una parte poco conocida de la historia

personal de alguien se convierte en una canción sesenta años después o más,

cantada en un lugar diferente por personas ajenas al suceso.

La canción trata sobre un misionero capuchino español en la

isla de Yap, Carolinas a fines de la década de 1890 y principios de la de 1900.

Su nombre era Padre Daniel de Arbácegui. En chamorro, Daniel se pronuncia

Daniet.

Había una pequeña comunidad de chamorros de Guam viviendo en

la isla de Yap desde la época española y estaban cerca de los misioneros

españoles.

Un niño chamorro de unos 6 años perdió a ambos progenitores

y fue criado por Påle' Daniet. Pero luego los alemanes tomaron la isla de Yap y

los misioneros españoles tuvieron que irse. En algún momento, el pequeño se

mudó a Saipán, Marianas.

La historia la guardó Juan Sánchez, un escritor, poeta y

cuentacuentos de Saipán muy cercano al clero. Alex Sablan, el compositor y

cantante de la canción, aprendió la historia de Juan Sánchez.

POR SI ACASO...

Hubo otro niño en Micronesia criado por los capuchinos

españoles. Su nombre era Miguel de la Concepción. ¿Era éste el mismo niño

criado por Påle' Daniet? Tengo mis dudas.

En primer lugar, el niño de la canción era de la isla de Yap

mientras que Miguel de la Concepción era de la isla de Ponapé, también en

Carolinas. Påle' Daniet fue misionero en Yap y nunca se quedó en Ponapé, de

donde era Miguel. Finalmente, el niño de la canción se mudó a Saipán, Marianas

pero el niño Miguel se mudó a Manila, Filipinas donde los frailes españoles lo

criaron. Pero... creo que deberíamos dejar algo de margen a la posibilidad de

que el niño huérfano en cuestión sea Miguel de la Concepción y que, como suele

pasar, la información oral que se transmite de persona a persona, confunda algunos

detalles.

Ésta es la letra de la canción de Alex Sablan basada en la

historia de Juan Sánchez: