Benjamin Lizama Torres (1884-1968)

Chamorro Whaling Crew

We have heard for many years now about the Chamorro boys and men who joined the American and British whaling ships.

But we know the individual stories of very few of them.

Here's one of these precious few stories.

Benjamin was born in Saipan in 1884, according to his wedding certificate. Unfortunately, there is no Benjamin Lizama Torres in the Saipan baptismal records. Perhaps the priest at the time just overlooked recording his baptism. Perhaps the family moved temporarily to Guam and Ben was born there.

However, we do find the baptismal records in Saipan of two of Ben's sisters, and from those records, we see that Ben's father was Joaquin Camacho Torres, born on Guam, and his mother was Dolores Crisostomo Lizama, also born on Guam.

According to the family, Ben had no brothers but he did have five sisters. Evidently, something happened in the family. We're not sure what happened but it is possible that mom, dad or both mom and dad died and Ben was sent to live in different homes, possibly relatives but we're not sure of that.

The young Ben did not like his life situation and got the idea, with a friend in tow, to sneak on board a whaling ship visiting Saipan and leave the island forever. He was 14 or 15 years old.

Hiding on the ship, the two boys were discovered only when it was too late for the ship to turn back to Saipan and return the boys. The captain took Ben under his wing and someone else did the same with the other boy. The captain put Ben to work as an assistant to the ship's cook. Ben would later work as a cook himself.

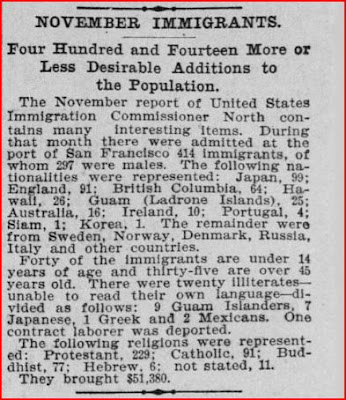

Eventually the ship stopped at San Francisco, California and Ben quit the whaling ship. He settled in San Francisco, working in different jobs. He married and had children.

Sometime later he moved to Hawaii, where his wife passed away. He found himself a second wife, a woman who had also lost her spouse in death. More children were born from this marriage.

As Chamorros from Guam joined the US Navy and came to Hawaii, Ben opened his home to them, especially for dinner during the holidays. Ben never lost his Chamorro language and spoke Chamorro with the Guam Navy boys. In his last days before he died in 1968, Ben actually lost his English and spoke only in Chamorro, even to his younger children even though they did not understand Chamorro.

Interestingly, two of Ben's daughters married Chamorro Navy men from Guam whom they had met while the men were stationed in Hawaii. One of these Navy men brought his wife, Ben's daughter, to Guam and then to Saipan, where she met her dad's youngest sister.

If anyone from Saipan is a Lizama Torres, descended from Joaquin Camacho Torres and Dolores Lizama Torres, please contact me. You have relatives in the mainland who want to connect with you.

I learned about Ben's story from his son, living now in California.