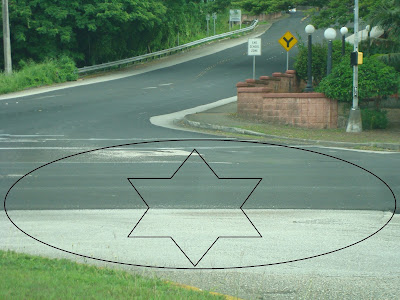

Poor Vicente never made it up this hill. He was shot and killed around this spot.

NOTE.

This is a historical account of a murder on Guam in 1900. The investigation records are still intact. But I am not including last names for the simple reason that 117 years ago is not that long a time. Relatives of the murderer, the suspected accomplice and the victim are still with us.

Vicente was, from all accounts, a nice guy. Sociable, affable and friendly. Except for a few landowners in Talofofo who differed with him about exact land boundaries, he got on well with everyone and even those neighboring ranchers didn't hate Vicente. It was just the normal squabbling about how far your goat could eat the grass that was routinely found among people in those days.

Vicente's real problem was his wife Rosa. Lots of people in Hagåtña believed that she was unfaithful, carrying on with a certain Juan. Her boyfriend Juan was a single man, and ten or so years younger than her. She made all kinds of excuses never to follow her husband Vicente from Hagåtña, where they lived, to their ranch in Talofofo. One day she would say she was not feeling well; the next day it was because she had too much to do in the Hagåtña home. So, off Vicente would go to the ranch in Talofofo, and Juan the boyfriend would spend time with Rosa in the house while Vicente was gone. Juan made himself at home, going into any room he cared to enter.

Tongues wagged all over Hagåtña. It didn't help that Rosa's own cook swore that she caught Juan and Rosa in physical contact in the

bodega or basement. Some of her own children also stated that they believed their mother and Juan had something going on.

Matters turned worse when Vicente himself walked in on his wife and Juan, a

kompådre to them by the way, in each other's arms. A day or so later, Vicente confided to a few people that he was resolved to bring Rosa down to Talofofo to live there for a few years, to keep her away from Juan. Perhaps that's when Juan got the notion to kill Vicente, to put an end to the plan to keep Juan and Rosa apart.

A witness actually called Juan and Rosa achagma (achakma), the Chamorro word for illicit lovers

In the early hours of May 16, 1900, between 2 and 3 in the morning, Vicente and his wife Rosa readied some of their animals and bags and left their house in Hagåtña to go to Talofofo. Another Vicente, a house boy, went with them. Though it was in the dark of night, the moon was out and its light brightened the path of the travelers. They entered San Ramón barrio and were just passing the last house on that road, which leads up the hill to Sinajaña.

Just before the road rose towards Sinajaña, Rosa asked to stop. She needed to urinate. In the meantime, Vicente decided to have a smoke. He lit a match to light his piece of tobacco and out of nowhere shots were fired. Vicente was hit three times in the back. A bullet entered his chest, damaging some vital organs and arteries. He fell on his face, then turned to lie face up, and died.

Rosa cried for help, bent down to examine her husband's body, and saw that he was already dead. She departed to inform the authorities at the government offices in the

Palåsyo (palace).

The testimony says Vicente was shot in a spot just before the road rises up the hill

Vicente's body was taken to his home and laid out. People remarked that Rosa did not seem to be grieving. Then there was the matter of the house clock; some noticed that it was two hours ahead of time! Someone had pushed the time forward. Vicente never left Hagåtña for Talofofo so early in the morning before. Why now? Rosa said they left that early at her request, in order to travel while it was still dark and cool. Did Rosa push the clock two hours ahead in order to make Vicente rush, thinking that they had less time in the dark than in reality? The real time was 2AM; their house clock said 4AM. Dawn was coming; hurry!

Strange, too, that they should travel in the darkness while Juan, Rosa's lover, was on guard duty at the

Palåsyo. An American military man says he saw Juan leave his post in those dark hours, and then there was the sound of gun fire. Half an hour later, Juan re-appeared at his post. When some American military men examined Juan's gun later, they stated that the gun had been fired within the last 48 hours.

Map of Hagåtña a few years after the murder, showing the barrio of San Ramón

and the pre-war road leading up to Sinajaña

Juan was detained, but let go because of insufficient evidence. But people observed that Juan stayed away from Rosa from then on. Both sides of the family, Rosa's and Juan's, strongly advised them to keep apart. People were pointing fingers mainly at Juan, but also at Rosa, as being responsible for the death of Vicente.

Then a strong typhoon in November of 1900 brought Juan and the widow Rosa together again. Juan went to go see how Rosa fared the storm. In no time Rosa was pregnant, with Juan's child.

The authorities never let all of this pass, however, and by April of 1901, both Juan and Rosa were held in custody, while the government investigated further. Juan and Rosa denied any participation whatsoever in the murder of Vicente, but, on April 4, Juan broke down and confessed to being the murderer of Vicente.

Juan blamed it all on the rage he felt when he happened to see Vicente and Rosa in physical intimacy in the privacy of their bedroom. This rage, Juan said, clouded his mind and he resolved to kill his lover's husband. Passing their house the night of the murder and seeing the light on and the door opened, Juan stopped by and learned from Rosa that they were about to leave for Talofofo. Juan went to get his gun and hid in the bushes in San Ramón by the road that leads to Sinajaña. He shot Vicente when he saw the match light.

Juan was eventually condemned to death. Rosa was set free. Juan's legal counsel appealed the sentence. Under Spanish law, a death sentence on Guam was appealed to the higher court in Manila. But that court was no longer in existence under the new American judicial system in the Philippines. Guam was lost somewhere in legal limbo. The United States Congress had not yet instituted a clear court system for Guam. Without a higher court to appeal to, the Navy in Washington told the Governor of Guam that the best thing to do was cancel the death sentence for Juan. It was reduced to a life sentence and, in time, Juan was pardoned.

Modern map of Hagåtña showing the general area of the murder