The Road from Hagåtña to Sumay

My grandmother had a cousin whom we all called Auntie Måmmi'. Her name was Carmen Cruz, married to a Guzmán from Sumay. She was second cousins with my grandmother but for some reason they were more like sisters. Maybe it's because they were only one year apart in age. Grandma was born in 1899 and Auntie Måmmi' in 1900.

Part of this closeness between them was that Auntie Måmmi' would spend a lot of time at our house. I mean she would spend 2 or 3 weeks at our house; the house that grandma and her sisters and I lived in. There was no extra bed. Auntie Måmmi' would share the same bed with one of the sisters.

Auntie Måmmi' couldn't speak English very well. She spoke broken English to me, but it was good enough for me to get what she was saying. She would also interject some Chamorro, which was great because that's partially how I got my start learning a little Chamorro.

I always enjoyed her long-term visits. She did interesting and cool things, like chew massive amounts of betel nut, with the works :

pugua', pupulu, åfok and amåska (betel nut, pepper leaf, lime rock paste and chewing tobacco). She would spit this blood red juice into a Foremost milk carton stuffed with paper towels. She would drink water out of a

låtan dudu. She wore enough gold bracelets to open her own store. Though her ear lobes sagged with age and gravity, she wore earrings and put lipstick on.

Dudus biha. (Flirty old lady.)

But she was so interesting because of her stories. She loved to tell me her encounters with the

taotaomo'na. Here are some.

WITH THE GOVERNOR

I guess she was a socialite of some sort, being a

dudus lady. So when she told me that the Governor of Guam and his wife, sometime in the 1920s, asked her to accompany them to Sumay, I believed it.

She said they rode in his car, which had an open roof. It was dusk, the sun was setting and it was becoming perfectly dark. She was sitting in the back of the car, in a corner. The Governor and his wife were busy talking to someone else when she felt a presence next to her, standing outside the car but at her corner.

It was dark so she didn't see the features of this person standing next to her, but she had this feeling it was a strange person. The person started talking to her, but in a language she did not understand. And Auntie Måmmi' imitated the sound : bab bab bab bab.

In time, the Governor was ready to go and the driver started up the car and off they went, and Auntie Måmmi' did not say a word about it to the American Governor. Down they drove to Sumay along the road that you see in the photo above.

THE SPOOKY HILLS OF SANTA RITA

Auntie Måmmi' in fact married a Guzmán from Sumay and after the war moved to Santa Rita as all the Sumay people did on orders of the U.S. Navy.

As you may know, Santa Rita sits on the slope of Mount Alifan. Some of those houses there are right up against the mountain.

Auntie Måmmi' told me about living in one such house, with its back door facing the bushy slopes of the mountain.

Someone also living in the house, I forget who, would throw things into the bush behind the house, against the slope of the mountain. Then, when Auntie Måmmi' would open the back door when it was getting dark, she saw dark figures in the bush. There may have been more details to this story which I have forgotten. But the bottom line was that Auntie Måmmi' told the person to stop throwing junk in the back of the house. Apparently the

taotaomo'na were not happy about it and made their presence known to Auntie Måmmi' to let them know it.

DON'T PEE OUTSIDE GUAM MEMORIAL HOSPITAL

My mother's brother Ning, Auntie Måmmi''s nephew, once went to GMH for some reason. It wasn't because he was sick. He went there either to visit someone who was sick, or some other business. Well, he parked in the back where the terrain is very rocky with coral rocks. He needed to relieve himself and he figured he could just do it safely by the cliff line, where it is rocky.

The following day his one foot was ablaze with painful swelling.

It was my Auntie Måmmi' who told me about it. "

Isao-ña ha' si Ning!" "

It's Ning's own fault!" she said.

"

Sagan taotaomo'na i acho'," she said. "

Rocky places are the abode of the taotaomo'na."

SHE SAW WHAT I COULDN'T SEE

Later in life, Auntie Måmmi' became one of the first residents at Guma' Trankilo, a residential area for elderly people. I would visit her there and she always said Tomhom (Tumon) was rife with

taotaomo'na since ever since.

Tomhom had been a large Chamorro settlement long before the Spaniards came. Bones of our ancestors can be found everywhere underneath Tomhom's sandy soil.

Especially when it was dusk, I'd be sitting talking to Auntie Måmmi', with her facing the screen door many times, and she would interrupt our conversation to ask me, "

Håye ennao?" as she looked at the screen door. I'd turn around and see no one. "

Who's that?"

"

Tåya' taotao, Auntie," I would reply. "

There's no one."

"

Hunggan guaha!" "

Yes there is."

Then she'd look down or away. I guess whoever was there moved away.

I'd get a bit of chill but I never saw, heard or sensed anything.

Sometimes I wondered if it was just an old lady's imagination, or if my Auntie Måmmi' was something of an entertainer.

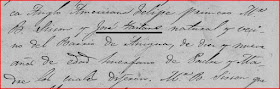

Auntie Måmmi' is the lady in front of the

haligi (pillar) facing the camera. The other lady is her cousin, my Auntie Epa', my grandmother's sister, Josefa Torres Artero, whom we called Auntie Epa'.

Taken at a picnic in the 1980s at Ipao in Tomhom -

sagan i taotaomo'na! Abode of the taotaomo'na!