Friday, February 20, 2015

CHAMORRO SERMON ON CONFESSION

Well, part of a sermon. From the 1960s

Un Påle' eståba na mamamaisen kuestion siha pot i katesismo.

(A priest was asking questions about the catechism.)

Måtto gi un dikkike' na påtgon låhe ya ha faisen,

(He came to a small boy and asked,)

"Juan, siakåso mohon na måtai hao yan un makkat na isao gi anti-mo, para måno hao guato?"

("John, suppose you die with one mortal sin on your soul, where will you go?")

"Siempre malak sasalåguan yo'," ineppe-ña i patgon.

("I will surely go to hell," was the boy's answer.)

"Pues håfa mohon para un cho'gue?" finaisen-ña ta'lo i Pale'.

("So what would you do?" was the priest's question again.)

"Bai hu konfesat," ilek-ña si Juan. Manman si Påle' ya ilek-ña, "Para un konfesat?"

("I will confess," Juan said. Father was amazed and said, "You will confess?")

"Måno nai un konfesat an esta hao gaige sasalåguan?"

("Where will you confess if you are already in hell?")

"Bai hu konfesat giya hågo," ineppe-ña i patgon.

("I will confess to you," was the boy's answer.)

Si Juan lache ni para u konfesat giya sasalåguan. Magåhet na yanggen måtai un taotao yan un makkat na isao

(Juan was wrong that he would confess in hell. It is true that if someone dies with mortal sin)

gi anti-ña, siempre u falak sasalåguan. Lao ayo ha' hamyo nai siña mangonfesat

(on his soul, he will certainly go to hell. But you can only confess)

yanggen man gagaige ha' hamyo trabia guine gi tano'.

(if you are still here on earth.)

Solo gi mientras man låla'la' hamyo.

(Only while you are alive.)

Thursday, February 19, 2015

THE LEGEND OF AS MÅTMOS

Many years ago, before the Spaniards came, there was a village on Luta called As Måtmos. Måtmos means "drown." The village is long gone, but the area is still called that today.

You might think the village was called by this name because it was located on a cliff by the sea. One false step and you could fall off that cliff and drown in the sea.

But the ancients have another explanation.

In those days, villages in our islands loved to compete. There were rivalries between chiefs, between father and son, and also between villages.

One day, the chief of the village eventually called As Måtmos challenged another chief of another village to see who could grow more rice.

Rice, as you may know, needs a lot of water to grow. Rice cannot grow on dry land, even if it is watered a lot. It has to grow in wet lands, like swamps.

Growing rice seedlings (få'i) in a rice field (famå'yan)

Well, As Måtmos is very dry and rocky land by that seacoast cliff. Try and try as they might, the people of that village couldn't create a rice field. But their chief kept pressuring them, so they wouldn't loose the competition and become mamåhlao (ashamed).

There are two versions of the conclusion of this story. The first is that the people of the village got fed up with their chief's insane ambition to win, which would have been impossible. So, they threw him over the cliff and he drowned. In the second version, the chief himself, seeing how it was impossible to grow rice in his village's bad terrain, threw himself into the sea and drowned.

In either case, the chief drowned and the place was known henceforth as As Måtmos, the place of drowning.

The rocky, sandy land of As Måtmos

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

ESTORIAN I KAKKAK

Kakkak

(Yellow Bittern - Ixobrychus sinensis)

An tiempon Kuaresma, manayuyunat i taotao.

(During Lenten season, the people fast.)

I man åmko' yan i man malångo u fañocho kåtne.

(The elderly and sick are to eat meat.)

Pues i kakkak ti malago' umayunat, sa' ma'å'ñao na u masoksok.

(Now the kakkak didn't want to fast, because he was afraid to get skinny.)

Pues annai måkpo' i Kuaresma, sinangåne as Jesukristo,

(So when Lent was over, he was told by Jesus Christ,)

"Ti un hongge i fino'-ho, sa' ma'å'ñao hao na para un masoksok."

("You didn't believe my word, because you were afraid that you were going to get skinny.")

"Pues tiene ke ni ngai'an na para un yommok."

("Therefore you will never be fat.")

"Masosoksok hao asta i finatai-mo."

("You will stay skinny till your death.")

- This was a story with a warning to those who did not faithfully observe the Lenten fast and abstinence rules.

- Another lesson to be learned was that when one defies God's law for some perceived benefit, one is stuck with that benefit in such a way that it turns into a liability. What you wanted as a blessing becomes a curse if it defies God's law.

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

SUPPLYING THE WHALERS

Although the heyday of the whaling era was already over, some foreign merchants thought there was still money to be made on Guam supplying the whaling ships and whoever else might stop by.

A Spanish pilot and merchant with business ties in the Pacific named Serapio San Juan opened such a business on Guam. The landing is described as Apra Harbor, but the actual store had to have been on land, so Sumay, Piti or Hagåtña are likely places.

It's quite an impressive list of items for sale, one that the European colony on Guam and perhaps some affluent Chamorros would have welcomed, except that the Spanish Governors usually wanted control over all commerce in the islands. I wouldn't be surprised if there was some quiet "arrangement" between San Juan and the Governor at the time, Pablo Pérez, who was a controversial figure.

Apparently, San Juan reached out to two people with money from opposite sides of the Pacific, probably to invest in his business and keep it alive with capital.

Martín Varanda was a Spanish businessman in the Philippines, and Francisco Rodríguez Vida was the Chilean Consul in Hawaii.

The business floundered and didn't last very long at all, perhaps just a year. San Juan's name shows up in press accounts and documents in Peru years later, after his failed Guam venture.

In 1850, San Juan got permission from the Spanish government to mine coal in Hågat, which I'm not sure even existed. Whatever dreams he had of making money in Guam coal never materialized.

The ads for his Guam business were placed in a Honolulu newspaper. Because of the whaling ships, a mercantile connection linked Guam and Hawaii for much of the 1800s. Because of that, a small colony of Chamorros ended up in Hawaii long before both Guam and Hawaii became part of the U.S.

*** Even years after Sanvitores changed the name of these islands to the Marianas, non-Spanish sources often still called them the Ladrones in the style of the older maps and books. This was often abbreviated as L.I. (Ladrone Islands)

The ads for his Guam business were placed in a Honolulu newspaper. Because of the whaling ships, a mercantile connection linked Guam and Hawaii for much of the 1800s. Because of that, a small colony of Chamorros ended up in Hawaii long before both Guam and Hawaii became part of the U.S.

*** Even years after Sanvitores changed the name of these islands to the Marianas, non-Spanish sources often still called them the Ladrones in the style of the older maps and books. This was often abbreviated as L.I. (Ladrone Islands)

Thursday, February 12, 2015

DESPEDIDA LETTER

Sometime after New Year's, 1972, Juan Aguon Sanchez, a well-known civic leader in Saipan, learned that the pastor of Saipan (it was all one parish then), Capuchin Father Lee Friel, was being transferred to Guam.

Sanchez was moved to write a farewell, or despedida, letter to the priest. His original letter is seen above. I will transcribe it using my orthography and supply an English translation :

I gine'fli'e'-ho na Påle'-måme gi papa' i månton Korason de Jesus.

(My beloved pastor of ours under the mantle of the Heart of Jesus.)

Dångkulo na hu agradese, Påle', todo i masapet-mo pot hame nu i famagu'on-mo,

(I hugely appreciate, Father, all your hardships for us your children,)

yan i Lorian Yu'us na Saina-ta, (1)

(and for the Glory of our Lord God,)

annai eståba hao guine gi parokian-måme.

(when you were here in our parish.)

Pues, Påle', hu gågågao hao gi todo i ha'ånen i tinayuyot-mo,

(So, Father, I ask you that in all your daily prayers)

na on (2) hahasso ham yan i famagu'on-mo siha, ya nå'e ham nu i bendision-mo.

(that you remember us and your children, and give us your blessing.)

Sin mås, Påle', adios ginen hame yan i asaguå-ho yan i famagu'on-ho.

(Without further ado, Father, farewell from us and my wife and children.)

NOTES

(1) Some Chamorros say gloria and others say loria, for "glory."

(2) On is an alternative for un (you, singular).

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

THE GUAM CAPUCHINS AND LOURDES

Dedication of OL of Lourdes Church, Yigo

May 5, 1965

The Capuchins on Guam established most of the parishes on Guam, but Yigo stands out in a special way because that church may never had been called Our Lady of Lourdes had it not been for the Capuchins, and perhaps because of one in particular, Påle' Román María de Vera.

Påle' Román

The idea probably came about in 1919, because by early 1920, Påle' Román was already preparing a young Yigo lady named Isabel Torres Pérez to recite the novena in Chamorro which Påle' Román had written. Besides the novena, Påle' Román composed the hymn to her in Chamorro, using a Basque church melody, and taught it to a small group of young Yigo maidens, mostly sisters from the Pérez (Goyo) clan.

A very rudimentary chapel, made up of free materials from Guam's jungles, was built for the small numbers of people in Yigo at the time. As the years went on, the population grew, as Yigo was prime farming land.

The temporary chapel built in Yigo right after the war in 1945

THE SPANISH CAPUCHIN DEVOTION TO LOURDES

The Spanish Capuchins who worked on Guam since 1915 were from the Basque country, in the north of Spain near the French border. They were so close to France that devotion to Our Lady of Lourdes was something easily planted in the Basque country.

Lourdes (at top of map) is not very far from Spain

When the Capuchins began a presence in Manila, Philippines, they set up a shrine to Our Lady of Lourdes in their church in Intramuros, and, when that was destroyed in World War II, moved it to its present location in Quezon City where it has become a National Shrine.

The Lourdes Devotion in the Capuchin Church in Manila before the War

This connection with the Capuchin Church in Manila before World War II is important because Påle' Román first served in the Philippines long before he came to Guam.

A REMINDER

When I designed the new friary on Guam, built in 2007, I wanted to remind us all of our traditional Guam Capuchin link to the Basque Capuchins, Intramuros, Påle' Román and Our Lady of Lourdes. So I had this simple outdoor shrine made for Our Lady of Lourdes, across the Friary chapel.

People see this shrine and think of Our Lady of Lourdes, but there's more to this than that.

I pass by and think of all those things mentioned above.

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

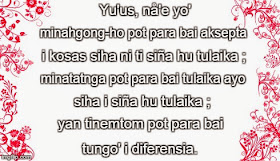

SERENITY PRAYER IN CHAMORRO

The English version is well-known :

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

the courage to change the things I can,

And the wisdom to know the difference.

NOTES

Nå'e yo' minahgong-ho. Måhgong means peace, tranquility, quiet. In Chamorro, when one asks God for this or that, the request is often expressed as "God give me my patience," or "my courage" and so on. Måhgong, by the way, is not the same as mågong, which means the easing of pain or illness.

Minatatnga. From matatnga, meaning boldness, fearlessness, courage.

Tinemtom. From tomtom, or wise.

Monday, February 9, 2015

ANNAI LALÅLO' SI PÅLE' SKÅT UN BIÅHE

Monsignor Oscar Luján Calvo

Although he was honored with the title Monsignor, Chamorros back in the day always called him "Påle' Skåt."

The Skåt was short for Oscar, shortened and pronounced the Chamorro way which changes final R to T. Like kolot instead of Spanish color. Under American influence, Skåt is often spelled Scott, but that just confuses people, thinking his actual name was Scott.

Påle' Skåt started out as a priest with a reputation for avoiding controversy. This he did with the Japanese when the Imperial forces occupied Guam during the war, and it saved his head, which was good for the 20,000 Catholic Chamorros who needed him!

In due course, however, time would prove that Påle' Skåt was not afraid of confronting publicly what he thought was unjust. The earliest example is when he lead a protest against the writings of George Tweed, the U.S. Navy radioman who was sheltered by the Chamorros the entire time of the Japanese occupation.

Right after the war, Tweed wrote a book, with the help of a professional writer. In that book, he made statements about both Father Dueñas and Påle' Skåt that were highly offensive to Påle' Skåt and others. Returning to Guam after that book was published, Tweed was greeted by a demonstration in the Plaza de España in Hagåtña, with Påle' Skåt at the forefront. Tweed later retracted his statement about Father Dueñas (but not about Calvo), saying that his ghost writer embellished the story and that he (Tweed) relied on what others said too much.

THE PDN LANGUAGE POLICY

Around 1977 or 1978, Påle' Skåt was at the forefront of another protest, this time against the "English only" language policy of the Pacific Daily News.

Chamorro language advocates were offended. They felt that the PDN should honor the Chamorro language which is indigenous to the island. When they felt that the PDN was not open to their arguments, they scheduled a protest.

THE PROTEST

The morning of the protest, which I believe was on a Saturday, I stood on the periphery of a crowd of 40-60 people who gathered on the public sidewalk in front of the Academy of Our Lady of Guam, facing the tall PDN Building. Protesters sang Chamorro songs and gave speeches in English and Chamorro. Indistinguishable faces peered from behind blinds and curtains from the PDN Building, including perhaps management which worked on the 2nd floor.

But the dramatic scene was saved for Påle' Skåt who climbed (with assistance) the raised platform and began his speech, again in both languages. Quite unexpectedly, he raised a copy of the PDN and, if memory serves, said into the microphone, "Here's what we think of your newspaper," and I suppose someone else (Påle' Skåt was advanced in age and nearly blind) lit a flame to the newspaper and set in on fire.

THE AFTERMATH

Within a week or so of this protest, the PDN changed its policy. Things could be published in the PDN in languages other than English, as long as there was also an English version of the same.

I am not sure now what is the PDN language policy today. I know that Peter Onedera has a CHamoru column in the paper, with an English version of it available on-line.

Once in a blue moon I will see a paid ad or notice (like funeral announcements) entirely in Chamorro.

Thursday, February 5, 2015

ETTON. NO, NOT THE ENGLISH SCHOOL ETON.

Some of the streets in some of our villages are named after long-forgotten areas in the outskirts of the village. Take, for example, Etton Lane in Sinajaña.

Few residents of Sinajaña know that Etton is actually the name of an isolated area in between Sinajaña and Ordot. Legally Etton lies in Chalan Pago-Ordot Municipality. But, in olden times, the area was considered part of Sinajaña, which itself was legally part of the capital city of Agaña,

Here's a map showing the location of Etton, encircled :

At one time, though Etton had ranch houses, some of them growing coconuts, probably for the copra trade. Here is a Spanish-era land document showing the owner having land in Etton, spelled Erton by the Spanish. Just think of Terlaje, also a Spanish spelling, though in Chamorro we say tet-lahe.

The Spanish above, starting with the word "Segundo," means :

"Second : a piece of land, with coconut plantings, situated in Erton.

MEANING?

Now rests one final question. What does "etton" mean?

It's such an old word, no one uses it any more.

But it means "obstacle, hindrance." We have Påle' Román's Chamorro-Spanish dictionary to thank for that information.

Now why should that area be called "obstacle" or "hindrance?"

Who knows? It's in a heavily forested valley. Perhaps difficult to access and that's the reason for the name. Or maybe not. Our ancestors did not write down the reasons for what they did or why they named things the way they did.